By Mark Cheney, Patrick Murphy, and Chiara Parisi

Introduction

California’s recent investment of over four billion dollars into community schools signals significant support for the community school model. The state views community schools as an evidence-based approach to improve the connection between schools, families, and communities to improve educational outcomes for all. The scale at which California is investing in its schools is unprecedented and the implementation of community schools and the state structures around them are works in progress. In its “Follow the Money” series, the Opportunity Institute (OI) is investigating the initial inputs and investments in the California Community Schools Partnership Program (CCSPP). Initial insights in the first three blogs of the'' series provide a quick overview of top-line indicators.

The first blog in the “Follow the Money” series investigates which Local Education Agencies (LEAs) applied for and received CCSPP grants in real time. It discussed the rates at which both planning and implementation grants were approved and dove into the demographic information of the schools receiving and being denied funding.

The second blog in the series further explores planning grants for schools without existing community school sites. It examined who received planning grants, what the planning grant funds were spent on, and what types of matching funds, if any, came from either the community or the district.

This third blog in the “Follow the Money” series, will take a closer look at implementation grants. It comes as California is in the process of accepting and reviewing the second round of applications for implementation grants.

Who received a CCSPP implementation grant?

OI’s first blog in the “Follow the Money” series outlines the initial information surrounding both grants. Implementation grants initially had an 84% approval and funding rate. More than twice as many planning grants (192) were approved than implementation grants (76). This disparity is most certainly due to the newness of community schools in California and will most likely change when the next rounds of implementation grants are approved.

An initial qualification for receiving an implementation grant was to have at least fifty percent of students be unduplicated. To improve equity, the CCSPP prioritized funding schools that enrolled at least 80% unduplicated students. When grants were initially approved and funded, 90% of the students at schools awarded implementation grants were unduplicated. Discussed in OI’s first blog, implementation grants are being directed more disproportionately to LEAs with higher portions of African Americans and Hispanic or Latino students. Those are two positive signs that the community school grant resources are being equitably directed to those who need them most.

As reported by the California Department of Education (CDE), 76 applications have been approved and funded. Of those awards applications, 10 went to county offices of education, 50 went to school districts, and 16 went to charter schools for a total of $611 million.

Like planning grant money, implementation grant money is being directed toward students who need it most, schools serving high concentrations of unduplicated pupils. Implementation grant applicants had average unduplicated pupil populations of 80% and implementation grant award recipients had average unduplicated pupil populations of 90%, both higher than the statewide average percentages of unduplicated pupils (63%). Schools who received implementation grant money also possessed higher percentages of students who identified as African American, Hispanic or Latino, or Asian than statewide averages.

Unlike the planning grants, LEAs with an existing community schools program are eligible for the program. The CCSPP program will provide funds for eligible schools for up to $500,000 annually per school site for up to five years. As a result, the total funding awarded can be considerable, with the average grant awarded in the first round being just over $8 million and the median amount being $4 million. Planning grants, on the other hand, are issued to LEAs with no existing community schools in place and they award no more than $200,000 per LEA.

There were some significant differences in what LEAs applied for and what they received. Overall, the state approved just over $600 million in this first round of implementation grant awards, roughly $100 million less overall than the total amount requested by applicants. Some received less than what they requested; for example, Oakland Unified School District was awarded almost $67 million for implementation grants, $13 million less than what they requested in their application.

In a few cases, schools were awarded more money than they requested. In fact, a majority of the applicants received an award that was greater than their request. This appears to be a consequence of an effort to standardize the award amounts, at least in part. The CDE included in its materials to the State Board (see California State Board of Education May 2022 Agenda) a schedule that assigned award amounts based upon the size of the school and implementation year. These amounts ranged from a 5-year total award of $712,500 for a small school (25-150 students) to an award of $2,375,000 for a large school (2,001 or more students). The application of this schedule appears to have had a substantial effect on the award, and by our count, seven applicants received more than $1 million beyond what they requested.

The application of the schedule had a second consequence that distinguished this round of implementation grants from the first round of planning grants. Because of the provisions of the legislation and how it was implemented, planning grants could be awarded to a single charter school for the maximum amount, $200,000. The maximum planning award for a school district with multiple schools, however, was also $200,000. The result was a significant disparity in the dollars available from a per student served perspective. This round of implementation funding, which calculated the award amount based upon the number of eligible schools and the size of those schools, resulted in less disparity in terms of funding per student served.

What will the implementation grants be spent on?

LEAs submitted implementation grant applications with specified budget items for which this award would be used and those details varied in specificity. Some submissions spelled out precisely how much would be spent on specific items, but many did not. For example, one LEA lists budget items, but associates no dollar amount with each budget item:

Salary of one Counselor who has a deep SEL background to do the work of a TK-8th grade school counselor. Funding for [additional] days of psychology services from the county. School admin and teacher time will be allocated resources from the district to match requested grant funds and successfully implement the Phase I program.

Although this LEA listed a total of $492,367.52 toward spending on “Certificated Personnel Salaries”, there was no itemization of this total. The lack of specific attribution of dollar amounts to budget items presents a challenge to more precisely define how much, total and percentage, is spent on specific items.

Another example of missing, incomplete or incorrect data occurred with some LEAs who detailed the amount spent on specific budget items but did not have totals that matched the grant money associated with line of spending. For instance, one LEA listed $375,000 toward five-year spending for “Certificated Personnel Salaries” but only accounted for $80,750 in their budget description. CDE and CCSPP in coordination with the Technical Assistance Centers (TACs) should consider establishing how faithful these applications must be upon submission and then reconcile them with final spending. This reconciliation will add another layer of accountability straining an already stretched state budget. Neglecting this final reconciliation might be cost effective for the current budget, but hinders those attempting to ascertain which programs have the best return on their investment.

The implementation grant applications break spending into six categories: Certificated staff; classified staff; employee benefits; books and supplies; services and other operating expenditures; and capital outlay, but this research simplifies those six into three categories: staff, stuff, services.

Staff accounted for 69% of all budgeted spending. Community School Coordinators were the most commonly listed position (seventy percent of all grant applications). Other common budgeted positions are family and community engagement liaisons, social workers, school counselors, teachers, and paraprofessional educators.

Services accounted for 28% of budgeted spending. Professional development was commonly listed in the services category. Other popular budget items are community school consultants, creating family engagement networks, third party contracts with medical, mental, and dental health providers, Sown to Grow whole child support system, and services to support families like babysitting for parents to attend meetings and translation services.

Accounting for the smallest portion of spending is Stuff (3%). Books and supplies were the most common items in this category. They were often in reference to wellness centers, socio-emotional learning, parent and community engagement centers. Other common items were curriculum, supplies, and materials and were dedicated mainly to classroom instruction, socio-emotional learning, restorative justice, family/community engagement or professional development. Again, all of these elements comport with the concept of community schools as defined by the CDE.

Capital Outlay, the second part of the stuff category, was not a common budget item. It occurred twelve times among the 84 applications, but only five of those mentions had a dollar value listed for the grant money. Presumably, the capital outlay money from the other seven mentions should be coming from either community or district matches.

Looking at the data from a different angle tells us to what extent a school’s spending fulfilled the critical components of the community school model. Collaborative leadership practices were the most addressed budget item. Establishing community school coordinators and creating a variety of professional development programs were the two most common examples of collaborative leadership practices addressed.

Integrated student supports is the element addressed with the second most mentions. It is worth repeating that LEAs, to address whole-child equity, added staff positions like therapists, counselors, and social workers or wrap-around services that address students’ dental, medical, and mental health.

Family and community engagement was also an important part of grant applications, and ranked third in terms of mentions. LEAs funded Family and/or Community Liaisons, welcoming spaces like parent engagement centers for families within schools, community partnership events, and parent education workshops.

Community and District Matching Funds

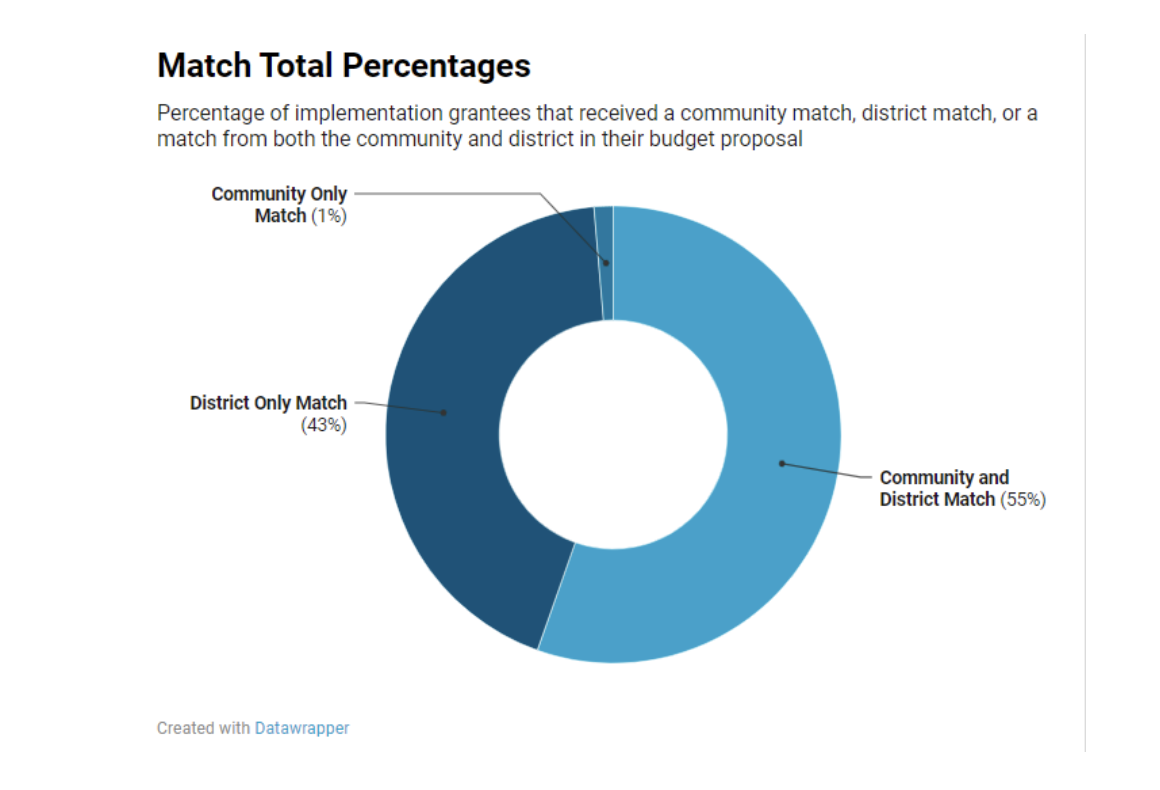

California recognizes the importance of braided and blended funding and community involvement to the success of community schools. Passed by the state legislature in 2021, AB 130 requires these grants to have a local match of at least one-third of the grant amount from the state. LEAs must work together within their community to ensure fidelity to the community school model. Requiring this investment deepens the community to school connection giving the community a greater stake in the school’s success. Local community organizations and school districts must be vested in these community schools for them to succeed and how better to show that investment than with funding, resources, and regular collaboration. Of the 84 LEAs receiving implementation grant awards, 45 had matches coming from the community, 82 had matches coming from the district, and 54 LEAs possessed both a community and district match. Future LEAs should recognize the importance of these investments and regularly seek them out. Creating positions like or similar to Community School Coordinators should afford schools the bandwidth to actively seek these investments from the community.

The detailed budget spending for implementation grants often did not distinguish grant funded items from match funded items, nor did it usually distinguish between community or district matches. When detailing budget items, most LEAs listed what the grant and match would be spent on together. Still, the grant and match money would be directed toward supporting the community school elements through various efforts including, but not limited to, funding parent and family engagement, professional development, socio-emotional learning, wellness/health checkups, reinforcement of restorative justice and trauma-informed practices, expanded learning opportunities, college pathways, and career technical education.

Looking Forward

The information provided in this brief offers a simple description of the first round of implementation funding and does not represent a deep dive into the success of the community school model in California as a result of this recent investment. That research will come much later. This review offers an overview of where implementation grants have been awarded, how grantees propose to spend the funds in their applications, and how robustly the community and/or district matched grant money. It also highlights the need to pay particular attention to elements of the community schools initiative going forward.

The critical role of the Technical Assistance Centers (TACs). The first round of CCSPP funds have been pushed out to the field quickly. Our review of the applications suggests that the grant recipients plan to use their new resources in a manner that generally aligns with the key elements needed for successful community schools. It is also apparent that moving from general plans to specific implementation will require assistance. The TACs are just starting to come online. Their ability to advise grant recipients about the myriad of implementation details likely to emerge in the coming months will be a critical determinant of the success of the community school model.

Data, reporting, and evaluation. What data will CDE, CCSPP, and the TACs rely upon to gauge the level of success for certain programs, interventions, and/or services? Data management must be an important aspect of every community school. Although less than half of LEAs specifically budgeted for data management and/or data analysis in their implementation grant applications, it will be important to be thoughtful, collaborative, and explicit about the data used to evaluate each community school. CDE and CCSPP must work in conjunction with the TACs and community schools to develop, enumerate, and cultivate this important data. TACs and LEAs must work together using the agreed upon data to evaluate programs and to make amendments to them when they fall short.

Mental health and other systems of support. Providing mental health and other services has become more central to the discussion of education in the wake of the pandemic. Eighty percent of the implementation grant awards mentioned funding for Integrated Support Systems. Though this high percentage represents an acknowledgment of the need to prioritize these services, realizing their integration into a school can be challenging. And the CCSPP will need to identify the role of community schools among other efforts to encourage interagency collaboration.

Career Technical Education (CTE). CTE has become an important part of public education. CTE or similar programs were mentioned in just over 10 percent of applications. Does its absence in most applications represent a missed opportunity to improve connections between the school and the community? Are there ways for the TACs to improve the connection between schools and the community through the creation of robust CTE programs?

Capital outlays. As community schools increase in size and scope, it is possible that LEAs might require creating new spaces or renovating current spaces to accommodate the services each site will offer. Few LEAs listed capital outlay (14%) as a budget item. As a result, site size and configuration limitations might present challenges to meet the increasing resources available at the schools.

Future fiscal challenges. California as a state could face significant fiscal headwinds in the future. The Legislative Analyst Office’s Fiscal Outlook concludes that the economic developments of 2022 have the potential to create a $25 billion “budget problem.” The Governor’s January budget highlighted a gap of a similar magnitude. OI’s own work on the topic notes that the future could be considerably worse. A downturn in overall state revenues has a direct impact on school funding. If districts face a decline in revenue in the coming year, will they be able to resist the temptation to backfill with other resources designated for other purposes – such as community schools?

The research analyzed in this blog confirms that these CCSPP grants are being directed toward the schools and students who need it most, and that the award recipients intend to use the funds to support the key elements of the community school model. Realizing those goals will depend mightily upon how the funds are actually used on the ground, beyond the broad categories outlined above. Ideally, California’s community schools investment will serve as the experiment that guides growth and adoption of the model beyond the state. For that to happen, it will be important to know which investments produced positive returns. Understanding how those resources are deployed, however, will depend upon more detailed reporting as well as a commitment to following the money. At this point, it is not certain those steps will be taken.